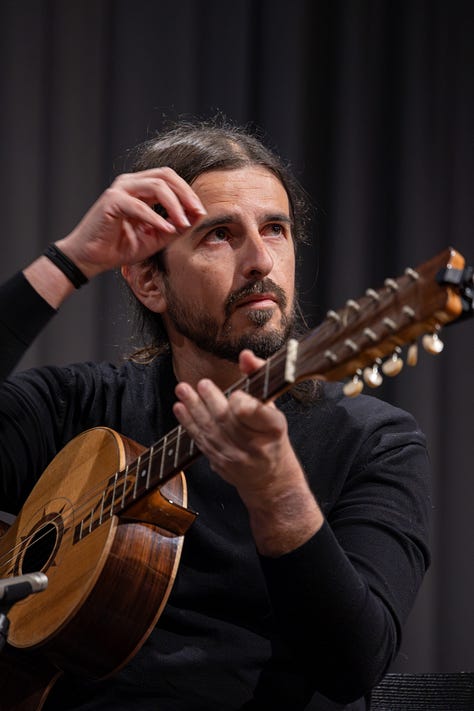

Welcome to the fourth issue of Amplified Silence, a monthly exploration of sound and listening. I'm Óscar Rodrigues, a musician and educator from Porto, Portugal and, each month, I'll share with you an essay (in the section called The Long Rest), three recommendations for things to listen, read, or watch (Harmonic Triad) and a list of upcoming events of my own (Signal Boost). Thank you for reading.

The Long Rest - Tradition in the Age of the Scroll

I'm writing this month's essay in a strange setting. It's April 28th, 2025, and Portugal is going through a general blackout. Communications have been down for more than eight hours, so we can't call anyone. No power also means no access to the internet or TV, and although radio still works, I don't have a battery-powered device at hand. I have no way of knowing what caused this, but that hardly seems important now.

Instead, what's striking is the sensation of being thrown back a few decades—a time before we were always connected. And yet, this isn't a nostalgic return. We remember that world, but we no longer belong to it. Our culture has changed. Constant connectivity has reshaped what it means to live, relate, and even think.

This moment feels like a coincidence, because I've spent the last month thinking about the relationship between tradition and technology. That was the central theme of the 2025 edition of the Porto Electronic Music Symposium, an international conference I’ve curated and hosted since its inception. It took place on April 26th at Casa da Música, bringing together concerts, talks, workshops, showcases, and a roundtable—all focused on this very question.

What emerged was a variety of perspectives: some grounded in folk or classical traditions that evolve through the inclusion of electronics; others aiming to break completely from the past. But through it all, one thing became clear to me: technology is not neutral. Every new medium, tool, or interface reconfigures our habits, aesthetics, and cultural assumptions. The blackout underscores this: being unable to contact anyone or access information reminds us how much of our world is built on technologies we take for granted—and how impossible it is to simply "go back."

It was through Neil Postman’s Technopoly that I first encountered the tale of Theuth and Thamus, from Plato’s Phaedrus, which I believe to be highly relevant.

In the story, the Egyptian god Theuth, inventor of many arts—including numbers, astronomy, and writing—presents his creations to King Thamus. Theuth praises writing as a tool to enhance memory and wisdom. But Thamus is skeptical. He argues that writing will actually weaken memory, encouraging forgetfulness because people will rely on written marks instead of internal recall. Rather than cultivating true understanding, they will only appear wise, repeating information without reflection.

"They will receive a quantity of information without proper instruction and, in consequence, be thought very knowledgeable when they are for the most part quite ignorant."

Thamus reminds us that every technological innovation brings both gains and losses. It’s not just about what a new tool allows us to do—it’s also about what it silently displaces. We might not notice what we’ve lost until, like today, the lights go out.

I've been playing the Viola Campaniça, a traditional instrument from Alentejo, in southern Portugal. It was once central to local celebrations, where people would gather to sing, dance, and improvise lyrics—what we call desgarradas—often using humor to mock friends and family. But as much as I engage with the instrument, I can't truly inhabit the life experience of those who originally played it.

My childhood was shaped by entirely different stimuli: I listened to music from all over the world, played video games, studied classical music, watched television, read science books—and lots and lots of comic books. The people who played the Viola Campaniça a century ago did none of that. Their world was smaller, but more grounded in a shared oral tradition. Mine was sprawling, mediated, global.

Similarly, I'm a huge fan of early polyphony. Viderunt Omnes by Léonin is one of my all-time favorite pieces. I often try to imagine what it must have felt like to hear two people singing different melodic lines at the same time—a radical innovation in the 12th century. But I can only imagine it. Why? Because my first cellphone had polyphonic ringtones. Every time someone called me, four different melodic lines would play simultaneously from a tiny speaker—while I stood on a city street, surrounded by traffic noise, airplanes overhead, and a TV murmuring in the background.

The sonic world I grew up in is completely different from that of someone living in a rural monastery outside Paris eight or nine hundred years ago. My experience of harmony is mediated by layers of technology, noise, and distraction. Their experience was likely one of reverence, clarity, and awe.

The power came back on, which means I can access the internet again and call my family. I'm relieved—everyone’s okay—but there’s a kind of calm that I'm sure some people will miss. It reminds me of the early days of the pandemic, when many of us reconnected with a slower, more intentional rhythm of life. Then we went back to doing the same things we were doing before.

Of course, we can still unplug. But the truth is, we don’t. Because our culture—our tradition, we might say—is already shaped by that constant connectedness. Being online isn’t a habit anymore; it’s the default.

I consider myself fortunate. Just a few days ago, and on the same day, I played the Viola Campaniça, then listened to Viderunt Omnes, watched a general rehearsal of Bruckner’s Fourth Symphony live, went for a run while listening to Anna Meredith’s Paramour, and ended the day with the Frozen II soundtrack playing in the background while spending time with my daughter. But even in that richness, I often feel I don’t have the time—or perhaps more accurately, the mental clarity—to let things really sink in. To try different things out, or to make mistakes.

Not all technological change is good, or even neutral. As Thamus warned through Plato, we often focus so intently on what new tools will give us, that we overlook what they might take away. And for me, one of the greatest losses has been control over our own time.

The blackout we just experienced shines a paradoxical, metaphorical light on that. In a world of permanent brightness and endless information, we may have gained access—but we lost depth. We gained data, but lost reflection. We gained information... and lost wisdom.

Harmonic Triad

As always, there's a lot going on in my mind, but I thought I'd explore some references that complement the previous essay. Here are my three recommendations for the week.

Anna Meredith

Anna Meredith is a Scottish composer and performer who first gained recognition through orchestral commissions, including works for the BBC Proms and a Concerto for Beatboxer and Orchestra. I first encountered her music about 12 years ago through a piece called Hands Free, written for the National Youth Orchestra. In this work, Meredith asked some of the UK’s top young classical musicians to put down their instruments and perform entirely using body percussion—focusing on their intrinsic musicality and the communal spirit of the orchestra itself.

The piece really resonated with me. At the time, I was beginning to explore community-based work and discovering the power—and accessibility—of body percussion, especially its deep connection with movement, rhythm, and groove. These are elements too often left out of traditional classical training.

Since then, Anna’s music has evolved to incorporate electronic elements. Her debut album Varmints is a great example—opening with Nautilus, a brassy, synth-laced piece that’s been reimagined in multiple formats, including an outrageous marching band version. She’s also worked in film scoring, interactive art music installations (check out Bumps Per Minute, a composition for bumper cars!), and visually striking orchestral works like Five Telegrams.

I recently met Anna and interviewed her for our PEMS conference. In our conversation, I asked her about a comment she made when Fibs, her second album, was nominated for the Mercury Prize: “It’s taken me a while to have the balls to write like this.” That line sums up a lot. Many artists coming from a classical background feel the tension between tradition and experimentation—between what shaped us, and what might hold us back.

Go and check out Anna’s music. :)

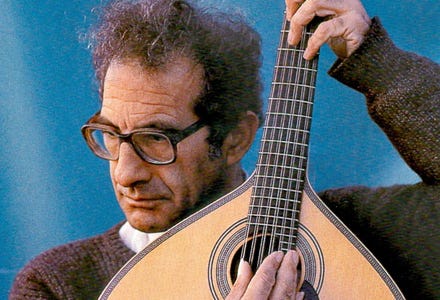

Carlos Paredes

Carlos Paredes was a Portuguese guitar player and a profound personal influence. He was born in February 1925, which means he would be celebrating his 100th anniversary this year.

The reason we chose this year’s Porto Electronic Music Symposium (PEMS) theme — the relationship between tradition and technology — has to do with two things. First, because it took place the day after the anniversary of the Carnation Revolution of 1974. (Carlos Paredes himself was arrested under the dictatorship for political reasons.) And second, because of the centennial of his birth. As part of this celebration, two of our concerts explored Portuguese traditional stringed instruments with electronics: Musiscópio, and a new duo performance by myself on the Viola Campaniça and João Diogo Leitão (the winner of the 2024 Carlos Paredes award) on the Viola Braguesa.

If you’re not familiar with Paredes’s music, the best place to start is the Portuguese Guitar itself. It’s a unique instrument — a direct descendant of medieval and renaissance guitars — with six courses (ordens, in Portuguese) of metal strings. Over time, it’s had many uses, most notably as the instrumental partner to the singer in Fado. But Carlos Paredes was not a Fado player. His approach was rooted in the Coimbra style, pioneered by his father, Artur Paredes.

It’s difficult to overstate Carlos Paredes’s importance in Portuguese music. He offered a refined, deeply personal vision of what it means to be Portuguese — one that transcended both the official state narratives of the dictatorship and the cultural expectations of Fado. Through timbre, harmony, phrasing, and rhythm, he carved out an expressive space that was uniquely his own. And he was a virtuoso, taking the Portuguese Guitar to places no one imagined possible.

Today, a new generation of immensely talented Portuguese guitarists continues to carry the instrument forward, including Miguel Amaral, who is also an excellent composer. But if you’re new to Portuguese music, Carlos Paredes is the best place to begin.

Mario Vargas Llosa - La civilización del espectáculo

Earlier this month, Mario Vargas Llosa, one of my favorite authors, left us. Just a few months ago, I reread his La civilización del espectáculo, a collection of essays and chronicles reflecting on the transformation of culture into entertainment. In this book, Vargas Llosa paints a sharp and often uncomfortable portrait of a society where artistic, intellectual, and even political life are increasingly shaped by the demands of spectacle, immediacy, and mass appeal. He argues that the pursuit of pleasure and distraction has replaced deeper forms of reflection and engagement, leaving behind a cultural landscape that prizes sensation over substance.

His concerns (and keep it mind that it was published 13 years ago, and some essays were written years before that) echo what we’ve been discussing — the tension between tradition and technology, and the subtle ways in which we lose depth while gaining access. In a world overflowing with content, it becomes harder to discern meaning; more difficult to make space for silence, ambiguity, or difficulty. Vargas Llosa’s critique isn’t a nostalgic lament, but a call to remain attentive — to preserve the seriousness, complexity, and responsibility that come with making and experiencing culture. For anyone reflecting on where we’re headed — culturally, artistically, politically — this book is a vital read.

Signal Boost

Upcoming events

Later today, April 30th, I'll go back to performing with João Diogo Leitão at Casa da Música's Clubbing. At the same event, Promenade, a concert happening on four different rooms at the same time, will be returning.

Next month, May 2025, will hopefully be a restful one. I'm taking a break from concerts and events to focus on composition, reading, trying things out.

Still, on May 17th, my new piece for Guitar Trio, A Terra Paga-me em Vida, will premiere at Ciclo Polinização, in Paredes de Coura, played by Francisco Berény, Hugo Simões and Rita Barbosa.

See you next month,

Óscar

Excelente ensaio! Obrigada